Walter Yeeling Wentz is born in Trenton, New Jersey. His father Christopher Wentz, born in Weissengen, Baden, Germany, had emigrated to America with his parents in 1846. Walter’s mother, Mary Evans Cook was a Quaker of Irish heritage. Walter had two brothers and two sisters.

Though initially a Baptist, Walter’s father had turned to spiritualism and Theosophy. As a teenager, Walter has a deep interest in the Bible, reads Madame Blavatsky’s “Isis Unveiled” and “The Secret Doctrine” in his father’s library and becomes interested in the teachings of Theosophy and the occult. Later he writes “I grew up as free as a pagan as any to whom St. Paul preached in Athens.” And “as I have held myself formally with no one country or race, so I have not allied myself formally with any of the world religions. I have embraced them all.”

1895

Influenced by the Theosophical readings, Walter is a recluse and considers this time his period of philosophical awakening. He enjoys being alone in the nature: “I would take off all my clothing and lie there naked as I was born with my eyes shut, sometimes thinking of nothing. I always felt, as I still do, a very intimate relationship between my body and the sun as the source of life energy… the magnetism from the earth under me and the magnetism from the sun above me filled my body with such freshness and vigor that I would return home calm and happy and well.”

In his unpublished autobiographical notes, written while in Sikkim in 1920, he recounts his first “ecstatic-like vision.” While alone on the upper Delaware River “in one of my secret retreats communing with nature… as I walked home slowly, I fell to singing a song of ecstatic rapture, composed as I sang it. There came flashing into my mind with such authority that I never thought of doubting it, a mind-picture of things past and to come. No details were definite, there was only the unrefutable conviction that I was a wanderer in this world from some far-off unfathomable and indescribably yet real realm; that all things I looked upon were but illusionary shadows. And there came to me a vague knowledge of things to be. I knew from that night that my life was to be that of a world-pilgrim, wandering from country to country, overseas, across continents and mountains, through deserts to the end of the earth, seeking, seeking for I knew not what.”

1898

Walter’s mother dies.

1900

Walter’s father marries his second wife, Olivia F. Bradford.

1901

Walter travels to San Diego and stays with his father, not far from Loma Land, where the Theosophical Society headquarters were located, and which he visits frequently. He is anxious to join the Society, but Katherine Tingley, the leader of the American section of the Society, encourages him to pursue studies at Stanford University.

1902

Evans-Wentz enrolls at Stanford University, where he studies religion, philosophy, and history and is deeply influenced by philosopher and psychologist William James and Irish poet William Butler Yeats.

1903

Walter notes in his diary that “I have been haunted with the conviction that this is not the first time that I have been possessed of a human body.”

1907

Walter studies Celtic mythology and folklore at Jesus College, Oxford, England. He does ethnographic fieldwork collecting fairy folklore in Wales, Scotland, Ireland, Cornwall, Brittany, and the Isle of Man.

1911

During last year at Oxford, Walter develops an interest in the study of religious experience. His degree thesis is published as a book, The Fairy-Faith in Celtic Countries. He receives the B. Sc from Oxford and a Doctorate from the University of Rennes, Brittany.

He adds his mother’s Welsh surname Evans to his name, being known henceforth as Evans-Wentz.

At Oxford, Evans-Wentz meets archaeologist and British Army officer T.E. Lawrence (“Lawrence of Arabia”), who advises him to travel to the Orient.

1913

His father renegotiates Walter’s real estate leases in America and his income increase from $400 a month to $1600, a significant amount at that time. He travels through Europe, and Rome brings back his disdain for the “hypocrisy of practiced Christianity.”

1914

The start of World War finds him in Greece. Visiting Delphi notes that “it is a rare privilege to visit the sites where great souls of the past have lived and thought.”

In September he is in Turkey doing anthropological research but due to war developments leaves the country for Egypt.

1915

Walter makes plans to travel to India, China and Japan, then to return home by April next year.

1916

Walter rents a place on the Egyptian coast near Alexandria, and spends his time studying Egyptian mythology. His Oxford mentor, Sir John Rhys and both his sisters had died, and Walter is newly inclined to a life of solitude “so I may go on free in body, in mind and in soul. This freedom is indeed the greatest of all blessings which come to man as man.”

T.E. Lawrence writes to Walter on December 16th, “there is no difficulty about getting to India. To be on the safe side we have wired to ask if they can allow you to wander about as you please.”

1917

On September 1st, Evans-Wentz boards a ship in Port Said for a three-week journey to Colombo, Ceylon.

Here he spends six months studying the history, customs and religious traditions of the country, and collects many important Pali manuscripts, which he donates to Stanford University and to local museums.

1918

Starting early in 1918, Walter travels across India, covering important religious sites, “seeking wise men of the east”.

At the Theosophical Society Adyar, he meets Annie Besant at the time when the Adyar Theosophists were preparing Jiddu Krishnamurti to become the Messiah, the new World Teacher, the incarnation of Buddha Maitreya.

1919

Walter visits Amritsar to study with the Sikhs, then goes to Prospect Hill in Simla, north of Delhi, a Theosophical pilgrimage spot, where H. P. Blavatsky claimed to have had her psychical experiences.

Swamy Syamānada Brahmacārī.

He travels around the foothills of the Himalayas by train, bus, horse or foot and meets local people and has lasting impressions. In Birbhadura, a small village on the Ganges, he meets sadhu Swāmi Satyānanda, who will have important influence on his spiritual development.

Next, Walter travels to Benares, the holy city where many faithful went there to die, where cremations went around the clock and even a widow could be seen throwing herself or being thrown on her husband’s funeral pyre (sati, or suttee).

Walter meets Swamy Syamānada Brahmacārī, who Evans-Wentz describes as someone who “harmoniously combines the power of spirituality with power of intellect and is representative of the karma yogi, who although living in the world, has not followed the path of the householder.”

Next, Walter travels east to Bodh Gaya, the holy place of Buddhism. He finds the place “unsanitary and full of smells. In possession of Hindus… Buddhists are outcasts in most holy seat of their religion.”

In Darjeeling Evans-Wentz meets Sardar Bahādur Sonam W. Laden La, a highly honored police officer, a Buddhist and multi linguistic personality who was fluent in English, Tibetan, Hindi, Marwari, Bengali, Nepali and Lepcha. (Sardar Bahadur stands for “Kings Police Medal”).

Sardar Bahādur Sonam W. Laden LaLaden La introduces Evans-Wentz to learned lāmas and among them Lāma Kazi Dawa-Samdup, an English teacher and headmaster at Maharaja’s Boys School, in Gangtok, Sikkim. Samdup had been with 13th Dalai Lāma during the latter’s exile years in India in 1910; more importantly for Evans-Wentz, he had already worked as a translator with Alexandra David-Néel, the Belgian-French explorer, travel writer, and Buddhist convert, and Sir John Woodroffe, noted British Orientalist.

Evans-Wentz receives an audience with the Crown Prince of Sikkim, the brother of deceased Sidkeong Tulku and Walter’s Oxford friend. He is given access to the monastery libraries to read-in and approved to use the services of Lāma Dawa-Samdup.

For the next few months, Evans-Wentz spent morning hours before the opening of the school with Lāma Samdup working on translations of texts that he will later publish under four titles:

•The Tibetan Book of the Dead

•Tibet’s Great Yogi Milarepa

•The Tibetan Book of the Great Liberation

•Tibetan Yoga and Secret Doctrines

The translation of The Tibetan Book of the Great Liberation was also contributed by Sardar Bahādur Sonam W. Laden La, Lāma Karma Sumdhon Paul and Lāma Lobzang Mingyur Dorje.

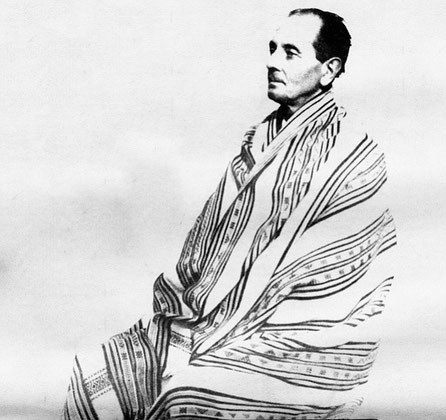

Lama Kazi Dawa Samdup and Evans-Wentz (circa 1919)

1920

Walter spends one day in Tibet, around Natu La pass, east of Gangtok. Lāma Samdup meanwhile is appointed lecturer at the University of Calcutta.

Evans-Wentz leaves for the Swāmi Satyananda’s ashram in Birbhadura, to gain “some actual insight into actual practice of yoga sufficient to enable me to continue the practice afterwards.” He follows Swāmi’s program to “neutralize the body” that consisted of sitting for four hours and forty minutes without moving. Only one meal a day and sleeping from midnight to six in the morning was permitted. After one year the yogi could start the prāṇāyāma practice.

1921

February, Walter’s father dies.

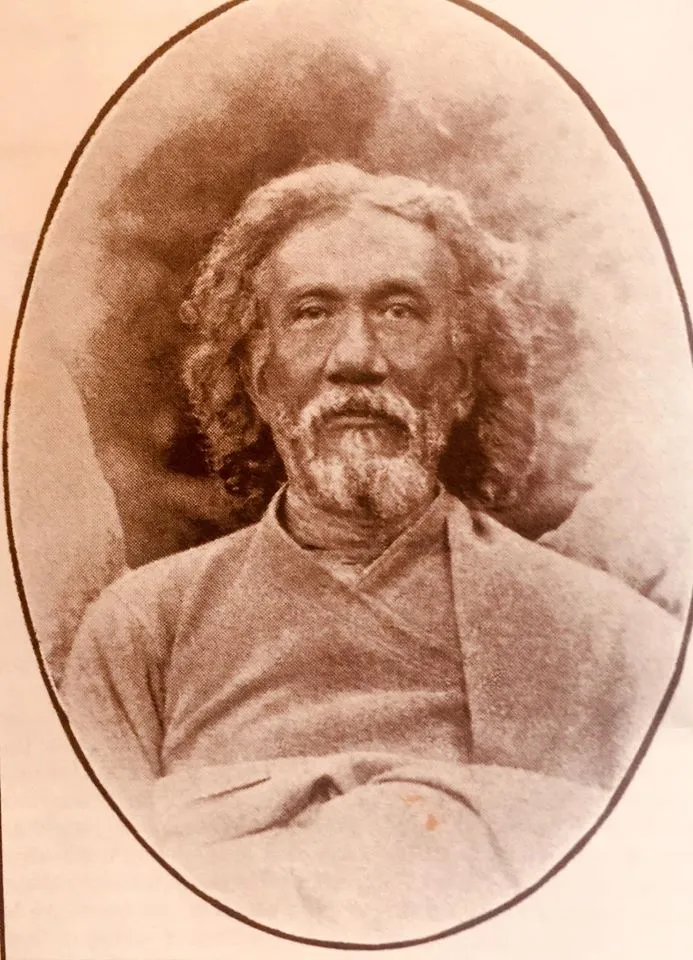

Swāmi Sri Yukteswar Giri

Walter travels to Puri, Orissa where he meets Swāmi Sri Yukteswar Giri, guru of Paramahansa Yogananda and Swāmi Satyananda Giri. He meets other teachers, later introduced in his book Tibetan Yoga and Secret Doctrines, that assist him in explaining doctrinal points from a Vedanta point of view rather than Buddhist.

Next, he travels to Nilgiri Hills, near Madras and studies the Todas, a Dravidian ethnic group.

In March he travels by boat to Trivandrum, on the south-east tip of India. He is looking for manuscripts and donates them to local museums.

Back in Ceylon, he writes to Dawa Samdup about his big fight he had with the Christian missionaries. “… I challenged the chief one to public debate, but he was too afraid to accept. The refusal gives me, so public opinion says, the victory…. You would have had a fine time had you been here to look on and give a speech or two.”

Like Colonel Olcott before, his support for Buddhism impressed the locals and disturbed the missionaries to the point where the latter requested the government to deport him, but without success.

1922

March 22nd, Lāma Dawa-Samdup dies in Calcutta.

Leaving Colombo, Walter travels to China to collect Tibetan manuscripts and Chinese paintings. He observes that “even the Chinese had caught the western disease for money-madness.”

1923

After a brief stop in Japan, Evans-Wentz arrives in Vancouver, Canada, then Seattle and finally San Diego to make arrangements for his father inheritance.

Walter has meetings with Katherine Tingley, the leader of the American Section of the Theosophical Society and founder of the Theosophical community Lomaland in Point Loma, California.

In a newspaper interview he states that “much of the western way of life is a waste of time. The western world seems filled with speculations of all kinds, real estate booms, oil development, mechanical inventions, which led to the obsession of money that possesses the occidental.”

1924

Evans-Wentz returns to Oxford and starts working on Milarepa biography and Bardo Thödol for being published, while following closely the translations of Dawa-Samdup.

In August Evans-Wentz travels back to Asia.

1925

In March, Walter is in Puri, India. Then via Calcutta goes to Darjeeling to help Dawa-Samdup family.

In May he arrives at Sadhana Ashram in Patna, then in Mussoorie, near Rishikesh.

In July he visits Swami Satyananda, but in August leaves the country, suffering of malaria, a condition he had most of his adult life.

October 3rd, at Oxford, Sir John Woodroffe writes a foreword titled “The Science of Death” to ‘The Tibetan Book of the Dead.”

1927

August 12, The Tibetan Book of the Dead (Bardo Thödol) is published. In the book preface he states that “the chief credit should be given to the late Lāma Kazi Dawa-Samdup, the translator… the Lāma himself aptly summarized the editor’s part in the work by saying that the editor was his living English dictionary.” Carl C. G. Jung wrote a Psychological Commentary.

In October Walter visits his brothers in New York and Los Angeles.

1928

In May travels back to East Coast and sails to England where he meets Jiddu Krishnamurti and they discuss Theosophy.

Tibet’s Great Yogi Milarepa is published.

In November Evans-Wentz is again in Ceylon, then in Puri.

1929

In February he is staying in Rishikesh and plans to open a yoga school in Puri where he previously purchased 1000 acres of land.

In March he considers giving the Puri property to Vidyāratna Pandit Maguni Brahma Misra, a karma yogin and Teacher of Ayurveda.

Travels back to Oxford, then India and then back to New York.

1930

By Christmas he is in San Diego and Point Loma, attending the funeral ceremonies of Katherine Tingley who died in a car accident.

1931

On January 14th, Evans-Wentz receives the Doctorate in Anthropology Science from Jesus College, Oxford.

The U.S. Government approves Evans-Wentz application to buy more land on mount Cuchama. He returns to San Diego to acquire 160 acres in addition to what he already owns. He intends to open a yoga school on this land, but feels that this goal is slipping away and that he cannot accomplish it alone, as “mankind is fettered, bantering away their bodily strength and health and length of days for things that pass away…”

1932

In summer, Walter is back in Oxford working on the manuscript of “Tibetan Yoga and Secret Doctrines.”

In October he meets with Gottfried de Purucker, leader of the Theosophical Society of Pasadena and former mentor of him, during the Society Convention in London and discuss the relationship between the Society and Buddhism.

1934

Walter writes the preface for the new book and leaves again for India. In an article for Times of Ceylon, he says “I feel there is something here in the way of a spiritual atmosphere lacking in Europe or America.”

In November he asks the British authorities to permit his pilgrimage to Mount Kailash and Lake Manasarovar, sacred in four religions: Hinduism, Bön, Buddhism, and Jainism. But his request is rejected.

Sri Ramana Maharshi in his late 60s

Evans-Wentz spends two weeks at Ramana Maharṣi ashram in Arunachala. Once he conversed with Maharṣi: “Which is most suitable time for meditation?” “What is time?”, Maharṣi replies. “Tell me what it is!”, Walter insists. “Time is only an idea. There is only the Reality. Whatever you think it is, it looks like that.”

He lives for some time in Almora, a village at the Himalayan foothills, where he acquires Kasar Devi estate, an area where he hopes to establish a religious center. Other Europeans live there at this time, among them Lāma Anagarika Govinda (Ernst Lothar Hoffmann) and Sunyabhai (Alfred Sorensen, also known as Sunyata and Shunya).

1935 – 1936

Walter spends several weeks in Ghoom Monastery, Dajeeeling editing the manuscript of “The Tibetan Book of Great Liberation.”

1938

Evans-Wentz is back in California where he keeps working on his manuscripts.

He gives his approval to the Ph. D. thesis of Theos Bernard, an explorer and author, known for his work on yoga and religious studies, who will later die in Punjab during violence associated with the partition of India.

In summer he travels to Oxford for the Tenth International Medical Congress for Psychotherapy. There he meets for the first time dr. Carl Jung. Jung promises to write a commentary to “The Tibetan Book of Great Liberation.”

1939

In May Evans-Wentz is back in Almora after a stopover in Egypt where he notes the “fear and hysteria” of the war.

1941

In January, Evans-Wentz writes his last will and testament.

Concerned that he could get stuck in Almora without financial means, he takes a ship to New York to avoid the Pacific and arrives in San Diego in June. Although he intends to be a temporary stay, he will never return to Asia.

He settles in the Keystone Hotel, in San Diego, close to the public library, the post office and a vegetarian restaurant.

1942

He writes that “whenever I am in the U.S. I fall under the influence of the worldly business environment to the neglect of spiritual studies.”

In May, The Theosophical Forum publishes his article on “The Science of Environment” where he describes his visits to sacred places, stating that “We await the awakening of all the races, of all the nations from the aeon-long sleep of Slothfulness and of Ignorance. We await the era of right education, when humanity will re-think and remake their world, when all places on the planet Earth, all the hills and mountains, all the rivers and lakes and seas, all the temples, all the cities, all the abodes will be holy, and divine at-one-ment will have been realized by man.”

He continues to purchase additional land from his neighbors around his ranch on Cuchama (Mt. Tecate).

1945

With the war coming to an end, Walter is still pessimistic:

“The nations are not prepared for world-wide altruism… old commercialistic greed is more likely to share the after-war world than the noble eight-fold path of the Buddha.”

1946

Evans-Wentz writes the preface to Paramahansa Yogananda‘s book Autobiography of a Yogi.

He mentions having personally met Yogananda‘s guru, Swami Sri Yukteswar Giri, at his ashram in Puri and notes positive impressions of him.

1948

In preparation for the second edition of The Tibetan Book of the Dead, Walter writes the new preface.

1949

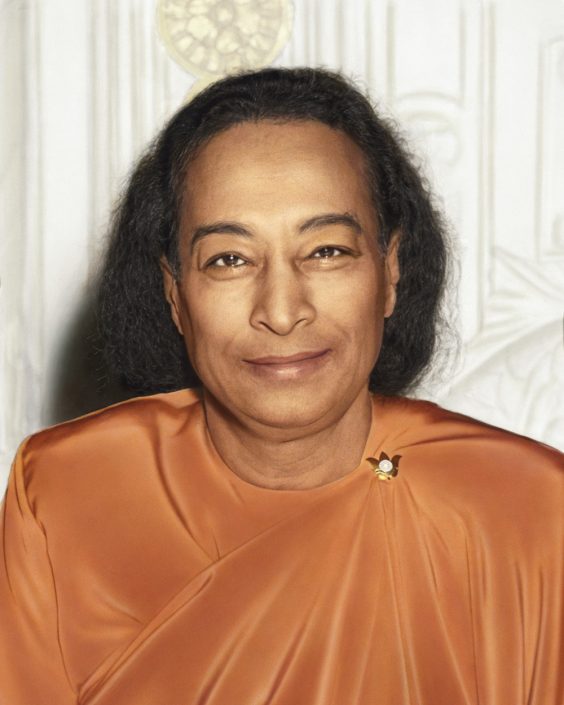

Paramahansa Yogananda, 1950

Yogananda spends some time on Cuchama, but also the world starts giving him more attention and Walter feels the stress of daily affairs. “More and more I feel the need to return to Almora and leave my bones in India.”

Second edition of The Tibetan Book of the Dead is published.

1951

Walter’s brother, James, dies in Florida.

Few months later, in March 1952, Pramahansa Yogananda dies also. Walter experiences a “crisis of unsettlement.”

While the third edition of The Tibetan Book of the Dead is prepared, Dr. Carl Jung offers his psychological commentary of the German edition to be used for this English edition.

A group from Brazil ask Evans-Wentz to be their guru, but he replies “I have been a little more than a transmitter of some of the lore of the Gurus. Look to yourselves.”

He makes plans to return to Kasar Devi in Almora, but the plans never materialize.

1954

The Tibetan Book of the Great Liberation; Or, The Method of Realizing Nirvana Through Knowing the Mind is published by Oxford University Press.

1955 – 1964

Evans-Wentz continues to write, study the Native Americans, travel to Mexico but he is “haunted by a realization of the illusion of all human endeavors. As Milarepa taught: buildings end in ruin, meetings in separation, accumulations in dispersions and life in death. Whether is better to go on here in California where I am lost in the midst of busy multitude or to return to the Himalayas is now a question difficult to answer correctly.”

1965

Before his own death in 1952, Paramahansa Yogananda offered Walter to live in his Self-Realization Fellowship ashram in Encinitas, California, for as much as time he would need. He spends his last months in a bungalow near the Fellowship.

Long suffering from a nervous condition, Evans-Wentz found himself increasingly more unable to write or take care of himself. His notes and his diaries became more and more difficult for the man himself to copy, let alone anyone else to read.

Walter Evans-Wentz dies on July 17, 1965. At his funeral Lou Blevens read from Tibetan Book of the Dead: “Oh nobly born Walter Yeeling Evans-Wentz, listen. Now you are experiencing the Radiance of the Clear Light of Pure Reality. Recognize it, o nobly-born…”

His ashes rest in a white stupa in northern India overlooking the “abode of snows,” the Himalayas.

Cuchama and Sacred Mountains is published in 1981 by Ohio University Press. The book explores the parallels between the spiritual teaching of native Americans and that of the Hindus and Tibetans.

Books